If Torture Means Compromise, Is Dying Gain?

What Happened When Wurmbrand Decided Suicide Was His Best Option

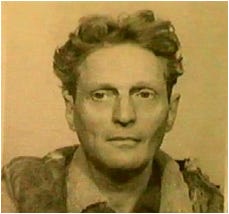

Richard Wurmbrand was a Romanian Lutheran minister who spent 14 years in prison (three in solitary confinement) and published ”Tortured for Christ" after his release in the late 1960s.

He later founded Voice of the Martyrs, but son Michael Wurmbrand does NOT recommend VOM’s ministry today. (Read his “Open Letter” about VOM.) Michael runs his own ministry, and has made most of his father’s books (and formerly unpublished writings) available for free!

What follows is from the first chapter of Wurmbrand’s book, In God’s Underground. You can also listen to the audio version of this post on the latest episode of the China Compass podcast.

Interrogation continued, month after month. You had to be convinced of your criminal past before Communist ideals could be implanted, and they took root only when you had succumbed to the belief that you were entirely, endlessly, in the Party's power and had surrendered every fragment of your life.

It was said now in Rumania that life consisted of the four "autos": the autocriticism that had to be recorded regularly in office and factory, the automobile that took you to the Secret Police, the autobiography they made you write, and your autopsy.

Suicide or Compromise: A False Choice?

Knowing that torture lay ahead, I resolved to kill myself rather than betray others. I felt no moral scruples: for a Christian to die means to go to Christ. I would explain, and He would surely understand. If St. Ursula had been canonized for killing herself rather than lose her virginity to the barbarians who sacked her monastery, then my duty to protect my friends was also more important than life.

But how was I to secure the means of suicide before my intention was suspected?

Guards checked prisoners and their cells regularly for possible instruments of death: glass slivers, a piece of cord, a razorblade. One morning, during the doctor's rounds, I said I couldn't remember all the details the interrogators needed because I hadn't slept for weeks. He prescribed a nightly sleeping pill and a guard peered into my mouth each time to make sure I'd swallowed it. In fact, I held the pill under my tongue and took it out when he had left. But where to hide my prize? Not on my body, to which anything might happen. Not in my pallet, which had to be shaken and folded daily. There was the other pallet in which Patrascanu had lain. I tore open a few stiches and every day hid another pill among the straw.

By the end of the month I had accumulated thirty. They were a comfort against the fear of breaking under torture, but I had fits of black depression at the thought of them. It was summer. I heard familiar sounds from the world outside. A girl singing. A trolley car grinding around the comer. Mothers calling their sons, "Silviu! Emill Mateil" Feathery seeds floated softly in to settle on my cement floor. I asked God what He was doing. Why was I being forced to put an end to a life which had been dedicated to His service? Looking up one evening through the narrow window, I saw the first star appear in the darkening sky, and thought that God had sent this light, which had begun its apparently useless journey billions of years ago, to console me.

The next morning the guard came in and, without a word, picked up the spare pallet with my hoarded pills in it and carried it off to some other prisoner. At first I was upset. Then I laughed, and felt calmer than I had for weeks. Since God did not want my suicide, then He would have to give me strength to bear the suffering ahead.

Terrible Tortures

The Secret Police had been patient, I was told, but now it was time for some results, and Colonel Dulgheru, their chief inquisitor, never failed to get them. He sat at his desk, still and menacing, with delicate hands spread out before him. "You've been playing with us," he said. In prewar days, Dulgheru had worked at the Soviet Embassy. Then, under the Fascists, he was interned along with Gheorghiu-Dej and other imprisoned Communists. They noted his strength, intelligence and ruthlessness. Now here he was, with delegated powers of life and death.

At once he began to question me about a Red Army man who had been caught smuggling Bibles into Russia. Until now the interrogators seemed to know nothing about my work among the Russians, but although the arrested soldier had not given me away, it was discovered that we had met. Now, more than ever, I had to weigh every word, for, in fact, I had baptized the man in Bucharest and enlisted him in our campaign.

Merciless Mind Games

Dulgheru's questions were persistent. He thought he had scented something important. In the weeks that followed I was worn down by a variety of means. The beds were removed from the cell and I had barely an hour's sleep a night, balanced on a chair. Twice every minute the spy hole in the door gave a metallic click, and the eye of a guard appeared. Often when I dozed he came in and kicked me awake. In the end I lost all sense of time. Once I awoke to see the cell door ajar. Soft music crept along the corridor: or was it an illusion? Then the sound grew distorted and became a woman's voice, sobbing. She began to scream. It was my wife!

"Please don't beat me. I can't bear it."

There was the sound of a whip on flesh. The screams rose to an appalling pitch. Every muscle in my body was taut with horror. Slowly the voice began to die away, moaning; but now it was the voice of a stranger. It faded into silence. I was left trembling, sweat-drenched, drained of feeling. Later I learned that the screams had come from a tape recorder, but every prisoner who heard it believed the victim to be his wife or sweetheart.