On my very first trip to China, way back in August of 2002, I spoke zero Chinese. ZERO. Well, that’s not entirely true. I could count to three: Yi – Er – San. And by the end of the two weeks, I think I knew how to say hello (Ni Hao) and goodbye (Zaijian). But that was it.

What saved me on that first trip, and what helped to jump-start me the following year when I moved to China was a little phrasebook created especially for zealous, yet illiterate, missionaries like myself. This phrasebook could be used in two basic ways: First, you could attempt to read the words out loud (usually a failure). Or Second, you could point to the phrase in question and let the other person read the words. This latter option served well in ordering meals, buying tickets, checking into hotels, etc. There was even an evangelism section at the back with simple “Gospel” phrases, such as “Jesus is the Savior of the world”.

But in early 2003, after arriving to stay in China for a year, and knowing that I would not be able to personally articulate the Gospel (or talk about much of anything, really) without learning the language, I dove into really studying Mandarin Chinese.

Learning by Immersion

The best way to describe my learning method is with the word “immersion”. I never took a proper language course, although our small team did spend a couple weeks with a Taiwanese Mandarin teacher who drilled us primarily on proper pronunciation. I would be amiss not say that this was indeed a tremendous help. In fact, I still praise that Taiwanese language tutor all the time..

Beyond that, however, I studied on my own while traveling in China, traversing the country numerous times (more than 120 cities!) in 2003. I learned to speak, listen (understand), and read (using a Bible, dictionary, maps, menus, signs) Chinese more naturally that way by chatting with people everywhere (even with homeless people at 4am). I studied on my own whenever possible (buses, trains, hotels, restaurants, the bathroom), sometimes late into the night and so intensely that my head would literally hurt and I would finally have to stop and go to sleep.

No Takers

I have often encouraged people to attempt to learn Chinese (or other languages) the way that I did, but almost nobody (that I know of) has taken me up on it. I guess it really does depend on the person. There are probably many who couldn’t learn Chinese in this way, but I am sure there are others (like me) out there who would likely learn a language quickly in this immersive (or, one might say “obsessive“) style.

One the greatest advantages of immersion is that from the beginning you are out traveling and spending time with real people, including among (if you want) some of the most unreached people groups in the world. In other words, from the word “go”, you can not only start learning the language, but also commence communicating the Gospel in some way.

But like I said before, it depends on the person. However, I do pray that more people would follow my lead and just jump in the deep end.

On Dictionaries and Pinyin

Two final thoughts:

Although my preferred learning method may not be for everyone, here are a couple of things I DO recommend for ALL Chinese language learners:

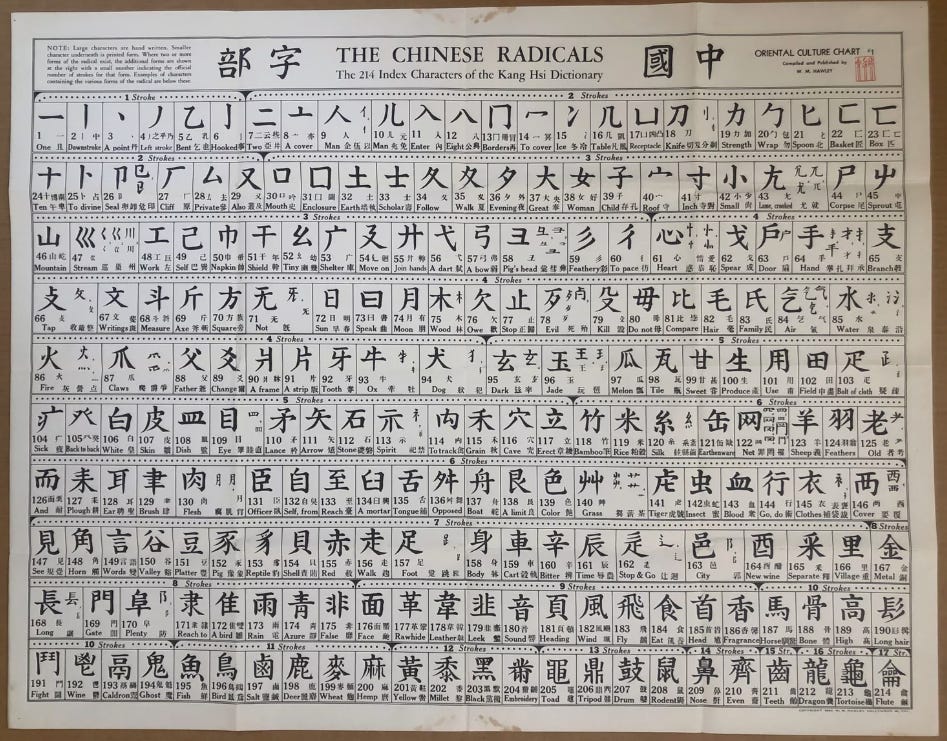

1. Force yourself to look up new words in a real, physical Chinese dictionary instead of using an electronic dictionary. The experience of endlessly searching for the correct ‘radicals’, and then skimming through thousands of characters looking for the exact one you are trying to locate, is immersion enough to cause the brain to hurt and to force you into the deep end, where your head will be swimming with Chinese. In other words, electronic dictionaries are simply too easy. No pain, no gain. Grab your dictionary and your Bible, a map, or a menu (or walk the streets looking at signs), then dive into reading Chinese. And don’t forget to try using the new words in your spoken conversations!

2. Study “Pinyin” if you must, but use it as a servant to help master spoken Chinese! Chinese is so rich and the phonetic Pinyin spellings are limited in conveying that richness. Knowing actual characters is so rewarding and helpful in truly grasping the deeper meaning of the language. Now that I know how to read Chinese characters, I hate reading something written only in Pinyin, because it’s hard to understand the context. It would be sort of like readingenglishwithoutanyspacesorpunctuation. It’s not impossible, but feels unnatural. The Chinese symbols say so much more! Don’t make Pinyin a substitute for learning to read actual Chinese characters.